19

Followers

19

Following

M Sarki

Besides being a poet with four collections published, M Sarki is a painter, film maker, and photographer. He likes fine coffee and long walks.

M Sarki has written, directed, and produced six short films titled Gnoman's Bois de Rose, Biscuits and Striola , The Tools of Migrant Hunters, My Father's Kitchen, GL, and Cropped Out 2010. More details to follow. Also the author of the feature film screenplay, Alphonso Bow.

Currently reading

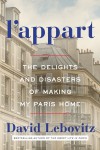

L'Appart: The Delights and Disasters of Making My Paris Home

We Learn Nothing: Essays

Elmet: LONGLISTED FOR THE MAN BOOKER PRIZE 2017

Limbo, and Other Places I Have Lived: Short Stories

The Double Life of Liliane

At Home with the Armadillo

American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank

Autumn

Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (Reading Edition)

American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank

The Naturalist: Theodore Roosevelt and His Adventures in the Wilderness

https://msarki.tumblr.com/post/161653555123/the-naturalist-theodore-roosevelt-and-his

https://msarki.tumblr.com/post/161653555123/the-naturalist-theodore-roosevelt-and-hisPerceived as a swash-buckling president, a rough rider, hunter, and preservationist dressed in a buckskin suit, Teddy Roosevelt has, in my lifetime, maintained his larger-than-life persona and for good reason. This book is the first study I have been subjected to regarding the man, and I could not have been more surprised over how much I did like him early on in my reading as I learned of his exploits, trials, and personal loss. Roosevelt like many others did not escape a lifetime of personal tragedy. He endured more than his share. And his evolvement as hunter to protector is of course as unsettling as it is amazing. Roosevelt lived in a vastly different time than we can comprehend fairly today. Financial and societal privilege afforded him many opportunities that most of us have only read about. But unlike others born into this privilege Roosevelt used his to further an agenda for good and to mark his time in history as significant and admirable. Theodore Roosevelt overcame poor health, a weak body, a childhood of city privilege and elitist pressures, to become a naturalist of the first rank. Focussing on the naturalist and human side of his subject Darrin Lunde provides his reader with a most-rewarding portrait of one of our country’s larger-than-life individuals who ever walked the earth.

After his evolvement as a naturalist and his two terms as president of the United States, Roosevelt seemed to change. And the last quarter of the book disturbs me to no small degree. What had previously come in the opening three quarters was a fascinating study of a man engaged with principal and courage. But beginning with the eagerly anticipated and extravagant African safari at the end of his presidency this endearing portrait of Roosevelt became a bit disgusting as he seemed to posture and demonstrate a pretentiousness absent in his early years. Cloaked behind a Smithsonian facade of scientific collection marched a loud and obnoxious cavalcade of pomp and bulge. For example, his sanctioned and personal killing of so many lions appeared to be wasteful, cruel, and extreme. Each subsequent page to follow felt uncomfortable. My disgusting reading about this particular safari was growing by the page and it became more difficult to remain enamored with the man who did so much to protect our lands. Though he did preserve a mass of wilderness for us, he failed in many respects to save the creatures inhabiting these spaces. Roosevelt was a hunter first who protected his sport through conservation. But, in fact, he was a killer of trophy wild animals who, with bad eyesight and poor skills, maimed and made suffer the most beautiful ones roaming the wild among us.

…Scouting around the first day, they saw seventy or eighty buffalo grazing in the open about a hundred yards from the edge of the swamp. It was too dark to shoot, but, heading out again early the next morning, Roosevelt and his party let fly a hail of ammunition to bring down three of the massive bulls.…It was a real chore for him to write in the field, and he joked that it was his way of paying for his fun.

What confounds me is the thinking that must go on in the head of any blood sport hunter. These men must have ignored the fact they were killing a creature that belonged on the planet just as much, or more, than they did. A wild creature of feeling, free to roam the plains being massacred by a privileged as well as massive and pretentious army hiding behind a cover of science, their rabid blood lust and joy celebrated on these killing fields. Conservation’s legacy handed down by Mr. Roosevelt is sadly tarnished by this horrid and destructive behavior not only by him but also by the hand of his son, Kermit.

…his Scribner’s accounts almost gave the impression that he was trying to provoke a reaction from the anti-hunting factions, as he documented his kills—botched shots and all—in unashamed detail…”I felt proud indeed as I stood by the immense bulk of the slain monster and put my hand on the ivory,” said Roosevelt, and then everyone began the work of skinning …

During this African safari Roosevelt and his companions killed or trapped approximately 11,400 animals, from insects and moles to hippopotamuses and elephants. In this biography Darrin Lunde has provided facts and story enough to honor Theodore Roosevelt as one of the most important naturalists who ever lived. And due to countless excesses he did help our evolving natural history museums to thrive. But at the cost of so many innocent and free lives, it saddens me.