19

Followers

19

Following

M Sarki

Besides being a poet with four collections published, M Sarki is a painter, film maker, and photographer. He likes fine coffee and long walks.

M Sarki has written, directed, and produced six short films titled Gnoman's Bois de Rose, Biscuits and Striola , The Tools of Migrant Hunters, My Father's Kitchen, GL, and Cropped Out 2010. More details to follow. Also the author of the feature film screenplay, Alphonso Bow.

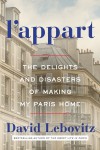

Currently reading

L'Appart: The Delights and Disasters of Making My Paris Home

We Learn Nothing: Essays

Elmet: LONGLISTED FOR THE MAN BOOKER PRIZE 2017

Limbo, and Other Places I Have Lived: Short Stories

The Double Life of Liliane

At Home with the Armadillo

American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank

Autumn

Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (Reading Edition)

American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank

Pereira Declares

http://msarki.tumblr.com/post/80156378904/pereira-declares-by-antonio-tabucchi

http://msarki.tumblr.com/post/80156378904/pereira-declares-by-antonio-tabucchiMy adventure in reading this novel Pereira Declares can be summed up by the word enjoyable. Antonio Tabucchi clearly bought me out completely. I loved every word of this translation. Though I am not, for the most part, political, I do empathize with the trying times of Portugal during this period in our world history, though I do not have a personal frame of reference for my understanding. I do hate all oppression and suppression, and believe I would fight to the death of me to protect my own independence and delusions of freedom I think I possess.

Having completed the reading now of a total of four novels written by Antonio Tabucchi I have discovered an interest in visiting Portugal, especially the city of Lisbon. Whether or not that happens for me depends certainly on my age and how long I have left to live on and in relatively good health. But I do have to say that the waters, the architecture, and cafes of this beautiful country beckon me. I am not, in particular, a cafe person, but when a place-setting exists, one that I might actually enjoy, I feel somewhat romantically drawn to it. Of course, my feelings can be swiftly rebutted or contained generally as soon as a loud and awful herd of humanity enters the picture. If I am not exactly a hater in the extreme sense then I am quite close to being one. But staying holed up in my apartment is not conducive to my living a good and complete life. Then again, Tabucchi's favorite writer Fernando Pessoa promoted his personal idea for always remaining inside the mind and to do one's traveling only within the realm of imagination. I do both and cannot really say which one works best for me. I suppose there is good and bad in everything. It is unfortunate that I am mostly disappointed in anything I have had hyped to me or been overly excited about. But to be honest it is I who is the one who hypes most persistently. It is a way to make a dull life more interesting. There is little reality to really get worked up over unless you are a person such as Pereira who just loves his cheese and herb omelette and his fresh-squeezed lemonade containing vast amounts of sugar. Tonight my wife and I will be dining at one of Louisville's best little restaurants called The Mayan Cafe. The owner/chef simply prepares the very best sauces that seem to explode on the tongue and these sauces give so much pleasure at times the experience feels unlawful. And his desserts are such fabulous and sinful creations that they are without a doubt worth breaking every dietary restriction previously and voluntarily adhered to.

I find it quite daunting to pin down exactly what made this novel so much fun for me to read. It was perhaps in the relaxed tone of the narrator Pereira and his ridiculous attempts, made half-heartedly and without conviction, in hopes of acquiring a more healthy lifestyle by losing a few pounds. The way he contributed financially, and almost without question, to the two young people caught up in politics Pereira himself had no interest in. It was also his gestures, quite sweet and innocent, as he employed and paid from his own pocket wages to the young journalist, receiving almost nothing in return that he could use worth publishing in his culture page. And in these feeble efforts Pereira's true character was revealed to me as it somehow projected his rock-solid conviction for doing the right thing, no matter what. The last few pages of the book move forward in almost blinding speed as the plot quickly thickens and rises to a boil that cannot keep itself from cascading over. A book so well worth my time to read, and with momentous flavors I still am savoring.